I would envision People living with HIV being part of the leadership of this community organizing effort. The UNAIDS developed an organogram in which all stakeholders were identified if we were to have effective and meaningful involvement of people living with HIV in aspects affecting them. The organogram lists the following levels: decision-making; experts; implementers; speakers; contributors; target audiences. These are the key community members, gatekeepers, or stakeholders I would particularly include.

A friend asked me to point out crucial relations between the language we use as we provide effective healthcare services in particular for People living with HIV. I suggested it was no less a language thing as much as it is mobilizing beneficiaries and providers around ensuring delivery of services that promote healthy outcomes. These can be the beginnings of a policy change itself. Social marketing, media advocacy and community organizing can be used to promote meaningful involvement of people living with HIV (PLHIV). It can be made an effective empowerment mechanism in giving feedback on how PLHIV are impacted by services they require e.g., health care, medication, housing, communication and modernization of policy. In using the three approaches, there are inbuilt advantages including cultural competency (Bentacourt J.R. 2005), tackling stigma and improving the quality of life for those living with HIV.

Through social marketing it is possible to influence practices at different levels e.g., decision-making; experts; implementers; speakers; contributors; target audiences (who are almost always not realized to be the subject matter (illnesses) experts). Social marketing, provides opportunities to implement practices by: accepting a new behavior, e.g., health facilities coming up with say, support meetings and regularized events for people living with HIV; reject a potential undesirable behavior, e.g., adopt language that is not stigmatizing of PLHIV; modify a current practice or behavior, e.g., encourage input in planning and managing of services by PLHIV; abandon an old undesirable behavior, e.g., using preferred language to reduce stigmatization of PLHIV such as adopting the use of terms like mixed status couple/serodifferent and not serodiscordant or use a people first language that emphasizes the person and not their diagnosis (Lynn V. 2016). Social marketing analyses neighborhoods or key populations and provides appropriate interventions (Farr, M., 2008). Social marketing promotes participation of consumers in designing mechanisms for airing out their own needs. It is also a mechanism for soliciting solutions from consumers. It sets the stage for healthy outcomes for all population groups and operationalizes policy for well being in society. Social marketing applies principles and techniques to create, communicate and deliver value to influence target audience practices or behaviors that benefit society and target audience (Correil, J., 2010) . For it to be effective, it employs the 4 P’s marketing mix strategies. By 4 P’s is meant: product; price; place; and promotion. It integrates the 4 P’s in any behavior change, maintenance or adoption strategy. Social marketing is employed in the following areas:

1. Health promotion-related issues such as: housing, fruit and vegetable intake, heavy binge/drinking, safety in cars, drinking and driving, storage of dangerous materials in homes, tobacco use, breastfeeding, obesity, teen pregnancy, STI’s prevention, oral health, immunization, diabetes, eating disorders and blood pressure.

2. Injury-prevention related behavioral issues such as: syringe exchange sites, decriminalization, safety in cars, drinking and driving, storage of dangerous materials in homes, avoiding falls in buildings, gun storage, domestic violence, injuries, drowning and suicides.

3. Environmental protection- related behavioral issues such as: waste reduction, wild life habitat protection, forest destruction, toxic fertilizers and pesticides, water conservation, air pollution, litter, avoiding unintentional fires and energy conservation.

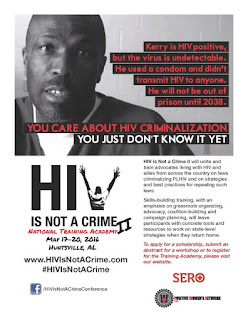

4. Community mobilization-related behavioral issues such as: safe drinking water campaigns, mosquito net use, decriminalization of HIV, blood donation, literacy, voting, animal adoption, increase utilization of public health services, combat chronic diseases and promote healthy living.

Media Advocacy, is when different communication means are utilized to deliver a message/s that promote/s healthy outcomes (Pérez, L., & Martinez, J. 2008). The communication means can be such as: news broadcast, social media, instant messaging, advertising, skits, information bulletins, public relations, social events, public meetings, exhibitions, sponsorships and use of platforms to continue with a given conversation on healthy outcomes.

Community organizing, is when communities are mobilized to address certain issues. This is effectively done when pretesting/piloting, monitoring and evaluation are integrated in strategies or initiatives (Pulliam, R. 2009). Community organizing is influenced by the social, cultural and regulatory environments prevailing to maximize effectiveness. The events around which organizing occurs may range from: modernizing laws, immunizations to treating Hepatitis. Community organizing is done to yield behavior change or maintain a positive practice (Galer-Unti, R. A., Tappe, M. K., & Lachenmayr, S. 2004). For meaningful involvement of people living with HIV, organizing is done around: core practice; actual practice; and augmented practice. The core practice in this case is: providing empowerment for PLWHIV to articulate correctly issues pertaining to them in an intervention planning event. The actual practice will be: creating space at the table for PLWHIV to bring their expertise. The augmented practice in this case can be: hearing first hand accounts that can be used to inform planning and policy.

References:

Betancourt, J. R., Green, A. R., Carrillo, J. E., & Park, E. R. (2005). Cultural competence and health care disparities: Key perspectives and trends. Health Affairs, 24(2).

Coreil, J. (Ed.). (2010). Social and behavioral foundations of public health (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Farr, M., Wardlaw, J., & Jones, C. (2008). Tackling health inequalities using geodemographics: A social marketing approach. International Journal of Market Research, 50(4), 449–467. Retrieved from the Walden Library databases.

Galer-Unti, R. A., Tappe, M. K., & Lachenmayr, S. (2004). Advocacy 101: Getting started in health education advocacy. Health Promotion Practice, 5(3), 280–288. Retrieved from the Walden Library databases.

Pérez, L., & Martinez, J. (2008). Community health workers: Social justice and policy advocates for community health and well-being. American Journal of Public Health, 98(1), 11–14. Retrieved from the Walden Library databases.

Pulliam, R. (2009). Developing your advocacy plan. Health Education Monograph Series, 26(1), 17–23. Retrieved from the Walden Library databases.

Vickie Lynn, Valerie Wojciechowicz. 2016. HIV Communication: Using Preferred Language to Reduce Stigma.